As we remember all those who have fought and died in wartime this Armistice Day, Professor Mary Davis reflects on the lesser known history of trade unions in wartime.

Date: 11 November 2021

The roots of the first majority Labour government 1945-1951 were to be found during the Second World War when, from 1940 Labour participated as a full partner in Churchill's coalition government. During the war Labour leaders not only acquired invaluable experience, after twenty years in the wilderness, of ministerial responsibility, but also helped to construct the collectivist practices of wartime which laid the foundations of the Welfare State. The wartime alliance with the Soviet Union whose decisive contribution to the defeat of fascism was widely acknowledged, lessened for a while the anti-sovietism and anti-communism which had pervaded the inter war years. In these conditions the post war domestic policies of the Allied powers were forced to pay regard to the needs of the masses to a greater extent than ever before. For Britain the political wartime consensus extended beyond state controls to social reform, enabling parliamentary labourism in the form of the first majority Labour government to reach its 'finest hour'.

Of the five members of Churchill's war cabinet formed in May 1940 two, Clement Attlee and Arthur Greenwood, were Labour MP's. Other Labour members held ministerial positions, the most important of whom in terms of labour relations was Ernest Bevin, Minister of Labour and National Service. Clearly Bevin's standing as leader of Britain's biggest trade union (the Transport and General Workers Union) was intended to deflect the kind of opposition to the control of labour which had been such a feature of the First World War. The measures introduced during this war were similarly draconian. The Emergency Powers Act and Defence Regulations provided the government with all the power it needed to direct and control labour. Strikes and lockouts were banned under Order 1305 and the 1941 Essential Work (General Provisions) Order allowed for the dilution of labour and the direction of skilled workers to wherever they were most needed. Bevin established a Joint Consultative Committee of seven employers' representatives and seven trade unionists to advise in the conduct of the war effort on the home front.

Until 1941 when the Soviet Union entered the war, communists in Britain, having little commitment to the war effort, refused to be bound by the national unity consensus and in particular the ban on strike action. During the first few months of the war, there were over 900 strikes, almost all of them very short but illegal nonetheless. Despite the provisions of Order 1305 there were very few prosecutions until 1941 since Bevin, anxious to avoid the labour unrest of the First World War, sought to promote conciliation rather than conflict. The number of strikes increased each year until 1944, almost half of them in support of wage demands and the remainder being defensive actions against deteriorations in workplace conditions. Coal and engineering were particularly affected. A strike in the Betteshanger colliery in Kent in 1942 prompted the first mass prosecutions under Order 1305. Three officials of the Betteshanger branch were imprisoned and over a thousand strikers were fined. Such repression and the general 'shoulders to the wheel' approach to industrial production in support of the war effort (strongly backed by the Communist Party after 1941) did not stop strikes. The fact that so many strikes took place in the mining industry was due in the main to the fact that the designation of coal mining as essential war work entailed the direction of selected conscripts to work in the mines ('Bevin boys'). This was very unpopular among regular miners.

In 1943 there were two major stoppages, one was a strike of 12,000 bus drivers and conductors and the other of dockers in Liverpool and Birkenhead. Both were a considerable embarrassment to Bevin since they involved mainly TGWU members. 1944 marked the peak of wartime strike action with over two thousand stoppages involving the loss of 3,714,000 days' production. This led to the imposition of Defence Regulation 1AA, supported by the TUC, which now made incitement to strike unlawful.

Trade unions (TUC affiliates) increased their membership by about three million during the war - from roughly four and a half million in 1938 to around seven and a half million in 1946 and this was accompanied by the spread of recognition agreements to industries in which unions had only a toe-hold before the war. To some extent this extension of trade union rights was underwritten by the government who denied war contracts to firms (under the Essential Works Order) who failed to conform to minimum standards demanded by the unions.

In 1941 the beginnings of TUC regional organisation was established (to operate in parallel to the Government's 12 defence regions), formally becoming TUC Regional Advisory Committees in 1945.

The People's War

Whereas the 1914-18 war was unpopular as a mismanaged fight between rival imperialisms, the war of 1939-45 was not perceived in the same way. The mass mobilisation of opposition to the Axis powers (Germany, Italy and Japan) was motivated by a higher ideal - the determination to rid the world of fascism. Of course, not every participant in the struggle was a conscious anti-fascist, but as news of the horrors perpetrated by fascism and the heroic resistance movements of nations under its control gradually filtered through, so the war itself took on something of the character of a 'people's war'.

The war itself, especially after the Soviet Union's entry, was a popular one. The German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, although not resulting in the opening of a 'second front', nonetheless prompted the government to send a flow of supplies and armaments via the dangerous Murmansk convoys. The TUC assisted this through its 'Help for Russia' fund and maintained close contact with Soviet trade unions through the Anglo-Russian Trade Union Council established in 1941. Until the end of the war, the anti-communism which had been the hallmark of the TUC leadership since 1926 was temporarily abandoned.

The Coalition government did much more than Lloyd George's administration to spread the burden of sacrifice (although it did not equalise it) through state controls and important measures of social reform. Such reforms included the provision of cheap school meals and day nurseries, improved pre-natal and infant welfare facilities and the abolition in 1941 of the hated 'means test'. Due to the sustained German bombing of urban areas (the 'blitz'), the government also provided emergency housing. In 1943 the main provisions of the Beveridge report, which laid the foundations of the welfare state, were accepted by the cabinet, although not acted upon until the war was over.

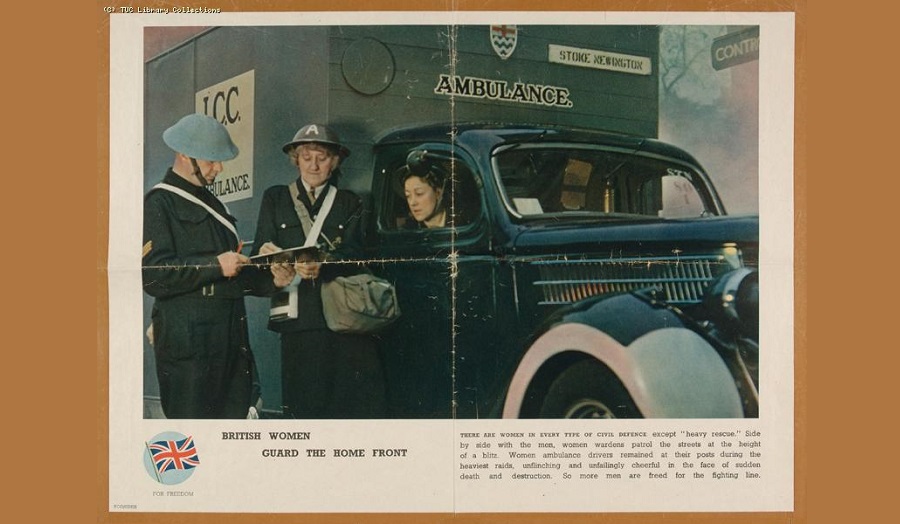

Women and World War Two

The war accorded women workers a high profile. Conscription for women was introduced in 1941. They had either to work in the munitions (or other designated) industry or were recruited into the Land Army. This did not mean that the state, in spite of some temporary concessions, had any intention of meaningfully addressing women's 'double burden'. An uneasy contradiction existed in the official mind between the obvious necessity to maintain wartime production on the one hand, and on the other the desire not to destabilise women's role in the family. It manifested itself in an unwillingness to ensure any lasting or general changes to the social order in favour of meeting the needs of working wives and mothers. Even the frequently cited provision of state day nurseries for working mothers, which was undoubtedly an historic initiative, was in itself the locus of intense ideological debate between realists like Bevin in the Ministry of Labour and the traditionalists of the Ministry of Health. Although the former appeared to win, as witnessed by the fact that 1,345 nurseries had been established by 1943 (compared with 14 existing in 1940), this did not represent a real victory for women workers. Firstly, it failed to satisfy the enormous demand or indeed to provide childcare for the duration of the mothers' working day, hence the great increase in private child minding arrangements and, secondly, it was always clear that this was a wartime expedient only - what the state provided the state could also easily remove.

There was discussion, although little action, on other ways to ease the double burden of women war workers. Sheer economic necessity forced such 'women's issues' as child-care facilities and maternity benefit on to the political agenda with undoubted advantages for women, albeit of a temporary nature, as the post-1945 period was to show. The more convenient and ideologically acceptable expedient of adjusting women to their double burden by permitting them to work part-time was the favoured alternative. Such a 'concession' was one of the few wartime changes which remains as a permanent feature of women's labour and of course helps to account for continuing low wages and lack of job opportunity.

This blog was written by Mary Davis, who was Professor of Labour Studies at London Met’s Centre for Trade Union Studies. It was first published on TUC History Online.

|

TUC Library Collections, London Metropolitan University |