Wendy Sloane, Associate Professor of Journalism at London Met, reports on how journalists in Russia have responded to the Kremlin’s clampdown on media.

Date: 16 March 2022

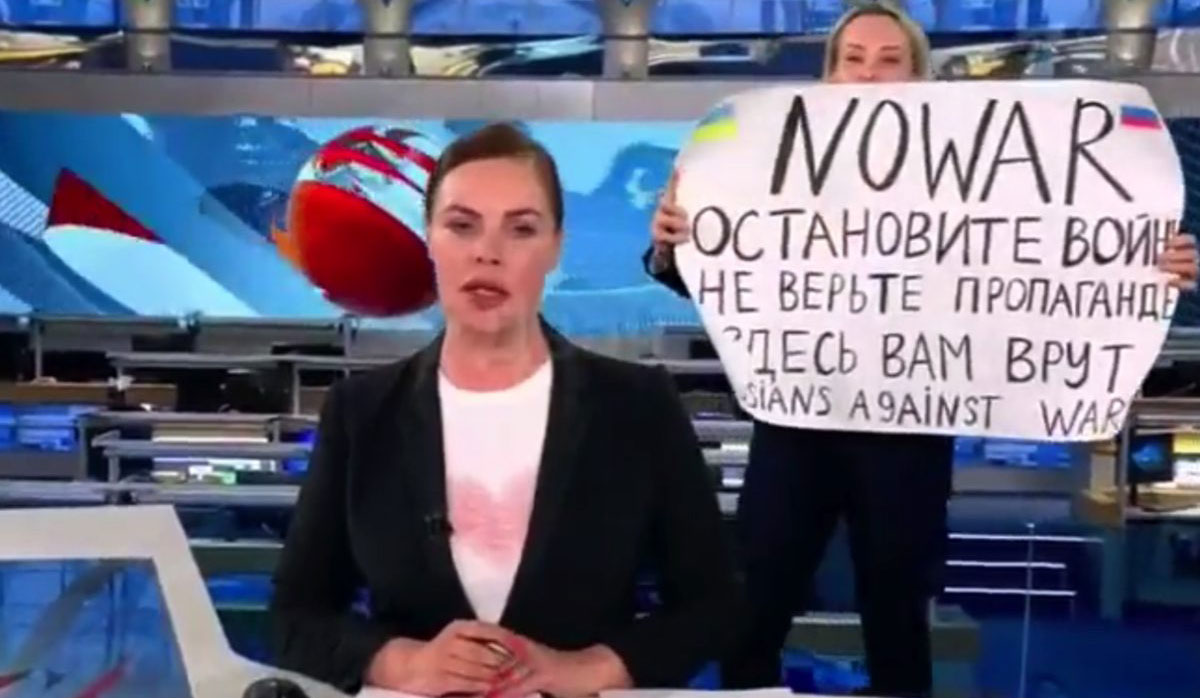

Russian rebel Marina Ovsyannikova was freed last night after bursting into a live state television broadcast holding up a sign against the war in Ukraine. But her widely shared act of protest is shining a light on how other reporters, both Russian and foreign, are struggling to cover the Russian invasion.

Ovsyannikova, who said she spent 14 hours being questioned by Russian police, was ultimately fined £30,000 rubles (£215) for her act of defiance, in which she held up a sign saying: "No War. Stop the war! Don't believe the propaganda! They are lying to you. Russians against war."

But while most Western outlets showed the poster in its entirety, Russia's independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta, found an arguably ingenious way to keep reporting the facts whilst sidestepping a new law on "false information" that bans reporters from using the words "war" or "invasion" to describe the, erm, Russian invasion.

On Monday, the paper, run by editor Dmitry Muratov, who won the Nobel Peace Prize last year, featured a censored version of Ovsyannikova's sign, with all the words blanked out except for "Don't believe the propaganda."

Novaya Gazeta "decided to stay [in Russia], to keep reporting, but they are saying that they are not breaking the law because they aren't mentioning the war or the armed forces," said Nanette van der Laan, a senior producer at Channel 4 News who was reporting from Moscow just last week.

The law, which came into effect on March 4, says that anyone using the words "war" or "invasion" when referring to Russia's "military operations" in Ukraine, or discredits the armed forces, faces imprisonment of up to 15 years.

Novaya Gazeta is doing its best to "channel its inner Basil Fawlty", said Van der Laan, who added that since Channel 4 News "could no longer do any original reporting and speak to people, that there was no point in staying in Moscow".

The decision to leave "was a very complicated conclusion that we took and we weren't happy taking that decision, and we left with heavy hearts", she added.

As more and more Western and Russian reporters flee Moscow due to censorship and safety concerns tied in with Putin's reporting clampdown, some are staying put and fighting the good fight – as much as they can. An estimated 200 foreign and Russian journalists have not fled the country, according to multiple sources.

Ovsyannikova's act of bravery could have cost her dearly: while she has been hailed as a hero in the West, some pundits feared for her physical safety, with France even offering her consular protection. Interestingly, her fine referred to a video statement she had made before her protest, in which she said that she was "ashamed" of working for the state channel and spreading what she called "Kremlin propaganda".

"Ovsyannikova is incredibly brave as she knew exactly what she was doing," said Van der Laan. "This will be a real test for the Kremlin. Obviously, she is the first person to really speak out since the Kremlin passed this new law."

Some pundits say there is still a chance Ovsyannikova could face more charges, especially as her lawyer, Pavel Chikov of the Agora human rights group, initially said that her arrest stemmed from charges of discrediting the military.

This morning on Twitter he talked about the psychological effect the war was having on journalists and activists, talking about "psychological assistance points" his group has opened for people in those professions who feel "anxious".

James Rodgers, author of Assignment Moscow: Reporting on Russia from Lenin to Putin and an Associate Professor of International Journalism at City, University of London, said it's "a very difficult decision" for journalists at the moment.

"In many ways, Russia is extremely newsworthy but it's also becoming an increasingly difficult environment for journalists to try and function in. In effect, the practice of independent journalism in Russia has become impossible due to the strictness of the new legislation," he said.

"In the early Soviet period under the Bolsheviks there were no foreign correspondents in Moscow and I fear we may see a return to that."

Michele Berdy, an American reporter for the independent English-language Moscow Times, was their Arts Editor and a columnist for the newspaper for years. Last week, she fled to Latvia: the paper is now being run from the Netherlands. "I lived in Moscow for more than 40 years. Last week I closed the door on my apartment and almost everything I have in this world," she told me.

"I desperately wanted to stay. But we all left because the new law on the media made it impossible to report openly or honestly without violating it. What's the point of talking to someone in person but not being able to report it?"

But Beth Knobel, a former CNN correspondent who worked as a journalist in Russia for 14 years and now teaches journalism at Fordham University in New York, wrote an opinion piece in the LA Times last Thursday in which she urged reporters to stay in Russia.

"With the Russian media almost completely under the thumb of the Kremlin, it is up to foreign journalists to document and report what is happening on the ground," she wrote. "The American and other foreign reporters staying in Russia may be taking a risk, but they are providing a crucial service to the world and the Russian people simply by reporting the truth."

Knobel later told me that she believes "a foreign reporter could stay in Russia and not go on air at all or publish anything but still be helping by monitoring the situation and submitting information to colleagues outside Russia".

Novaya Gazeta, which is not foreign but Russian, is doing a bit more than just monitoring the situation – but has received criticism that it's not taking a hard enough stance.

"[Aleksei] Navalny's people are fiercely criticising that Novaya Gazeta did the piece but blanked out her sign," said Van der Laan, referring to the country's main opposition leader, who is now in prison under Putin.

"They are saying this is incredibly cowardly, that after all this is Novaya Gazeta, the paper that Anna Politkovskaya [the assassinated activist] worked for and died for, and that they should not be censoring themselves," she said.

"Other people are saying no, what they are doing is really clever. By blanking out the poster, the readers will go: Wait – what is going on? Why is this blanked out? They might try to find out why the paper is censoring it."